The Farmer’s Rebellion Against Willem Adriaan van de Stel (1705-1707):

The Role of ‘The Nine’ Vrijboeren

by Marius Van Nieuwkerk

Previously released in Dutch:

in GENS NOSTRA, No. 2, 2017

Monthly journal of the Netherlands Genealogy Society (NGV)

https://ontdekjouwverhaal.nl/gens-nostra/

and on the website of the South African Literary magazine Litnet (Neerlandlit)

De Boerenopstand tegen Willem Adriaan van der Stel (1705–1707): De rol van “De Negen” Vrijboeren

Preface

In the summer of 1962 my older brother Gerrit emigrated to South Africa. Having just turned nineteen, he boarded the stately emigrant ship the SS Zuiderkruis. He wanted to go out into the wide world but did not want to go into the Dutch military. His choice for South Africa was not surprising. He had been corresponding with a minister’s daughter there and was a member of the accommodating Christian Emigration Centre of the Netherlands. Therefore housing and work – with the chance to study and good career prospects – were made available to him. After being employed by the South African Reserve Bank for a number of years, he opted for entrepreneurship. He died, far too young, in 2009.

Yet, what none of us knew when he emigrated was that almost three hundred years earlier, in 1671, a certain Cornelis Gerritzoon van Nieu(w)kerk had preceded him to South Africa. Faith (Church), Hope (work) and Love (contact) also played a significant role in that Van Nieu(w)kerk’s decision to emigrate. He too was closely affiliated with the church, could find sufficient work and housing through the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC or Dutch East India Company) and already knew a number of people there. Even more striking: thirty-five years after his June 1706 arrival at the Cape, the Castle of Good Hope’s bells rang out, followed by his name being announced along with those of eight other vrijburgers-cum-boeren (free burghers/farmers) or so-called vrijboeren (Lit. free farmers). This occurred during the reading of a proclamation denouncing ‘The Nine’ rebellious vrijboeren, which was subsequently posted in the towns of Stellenbosch, Drakenstein and Tygerbergen as well as ‘other customary places’ for all could see.

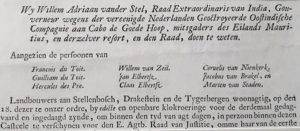

2. Part of the original Van der Stel proclamation

The Nine were subpoenaed and ordered for the third time to appear in person within eight days to be held accountable for ‘mutinous slander against the government. . .’ In this regard, the government meant Governor Willem Adriaan van der Stel, against whom sixty-three farmers had rebelled by signing a petition of grievances. The above Nine leaders did not want to be arrested or ‘compelled to repent’ so they were left with little choice but ‘to seek refuge in the wilderness’.

I dedicate this article to the memory of my brother Gerrit van Nieuwkerk (1943-2009) and to his family. My heartfelt thanks to the many contacts in South Africa and the Netherlands who provided me with their insights.

In the middle of the seventeenth century the board of the VOC or Dutch East India Company – known as the Heeren XVII (Lords Seventeen) – decided to establish a strategically located, fortified refreshment station at the Cape of Good Hope peninsula, the southern-most point of Africa. The VOC had already appropriated the islands of Saint Helena (1633) and Mauritius (1638) for the same purpose. The Heeren XVII chose Jan van Riebeeck to be the first Commander of the Cape, which led to his rehabilitation, given that a few years earlier he had been convicted ‘of private trade practices’ while he was a merchant in the employ of the VOC in Tonkin (Indochina).

Van Riebeeck arrived in South Africa on 6 April 1652 and after six weeks of hard labour his crew finished building the cube-shaped Fort de Goede Hoop (Fort of Good Hope). The primary purpose of this VOC post was to provide fresh provisions to VOC ships en route from Amsterdam to the capital city of Batavia (now Jakarta) in what was then the Dutch East Indies (today Indonesia). According to Van Riebeeck, free burghers were needed to populate and tame the hinterland: ‘Those serving the VOC will never work hard enough because they receive their salaries anyway.’ The first free burghers arrived in February 1657 and settled behind DieTafelberg (Table Mountain), where they started cultivating the land and raising livestock.

With the arrival of this group of settlers, the refreshment station became something of a colony. But these free burghers who worked as farmers were required to sell their products to the VOC – at extremely low fixed prices – and were prohibited from trading their livestock with the native population. The VOC ultimately had a monopoly and therefore its officials as well. With unlimited power to arbitrarily regulate all kinds of trade, the Company was also in a position to abuse that power. Van Riebeeck (1652-1662) exercised restraint in this regard, but this could not be said of all of his successors.

It was, however, no secret that these vrijboeren were not prepared to bow to all of the VOC’s rules. Less than a year after their arrival, they were already rebelling against the restrictions imposed upon them, and they were vocal about expressing this to Van Riebeeck: ‘We do not want to be the Company’s slaves’. Van Riebeeck understood this: in order to attract the right kind of people to settle at the Cape as free burghers, simply eking out a living from their land would not be enough. They would need the opportunity to prosper. Therefore new kinds of related activities were frequently permitted, if only ‘to reduce the Cape’s acute food shortages’.

Some years later, under the leadership of Governor Simon van der Stel (1679-1699) succeeded by his son Willem Adriaan (1699-1707), serious attention was given to the further development of agricultural production and other economic activities. The town of Stellenbosch – derived from Van der Stel name and the Dutch for woodlands – was a vibrant example of this. It had oak-lined streets, a newly constructed mill and a thriving wine industry. Today it is still considered one of the most beautiful places in South Africa. Nonetheless, one of the initial drawbacks under their rule was that revenues from these new economic developments were distributed rather one-sidedly, also given the two were busy acquiring a small fortune. Even today the private family estates of that era, Simon’s Constantia (www.grootconstantia.co.za) and Willem Adriaan’s Vergelegen (www.vergelegen.co.za), serve to reveal the extent of their riches2.

4. The VOC: Foothold in South Africa

Another drawback under their governance – no doubt related to their blatant greed – was that the relationship they had with the vrijboeren rapidly deteriorated. While as time passed visiting high-ranking VOC officials from the Dutch Republic seemed to look more favourably on these free burghers, and exhibited an understanding of the problems they faced, it was clear that the Cape’s rulers did not hold this group of colonists in very high-esteem3. Particularly Willem Adriaan – although a great lover of nature –exhibited, less admirable, despotic qualities as well. Catch phrases he often used illustrate this best:

- ‘Do they think they can teach me how to govern?’

- ‘. . . as if such a rotten bunch can be governed mildly.’

- ‘Eggs in the pan [= prison] puts an end to bad blood in the brood.’

Moreover, ‘Willem Adriaan’s private life was so depraved, whenever he was present at religious services he forbade the the Ten Commandments from being read aloud.’

The vrijboeren had no political power; those in service of the VOC at the Cape held the most important positions. In addition, much of the Company’s farmlands and livestock ended up in the hands of high-placed officials, supposedly through purchase. Consequently they were fierce competition for the vrijboeren. Indicative of this situation was the fact that a ‘civil servant clique’ of seven or eight people, which also included Willem Adriaan, his father Simon and his brother Frans, owned as much land as half of what all the vrijboeren at the Cape owned together. In addition, this clique misused its power to strengthen their near-monopoly. For instance, in 1702 the license the vrijboeren had to exchange livestock with the Khoikhoi (Hottentots) was rescinded, which put an end to their profitable barter trade. This made the famers furious, but their grievances were ignored; it was like getting blood from a stone. This anger was fuelled by two new incidents early in 1705. Four vleespachters – livestock farmers who had leased their land from the VOC – purchased the sole rights to provide meat for the garrison, but the civil servants’ clique would have control over the deliveries. After that Governor Willem Adriaan gave the sole rights to the lucrative wine trade to one person, a certain Johannes Phijffer. This man, one of the governor’s trusted associates, was in fact a convicted smuggler. It was the final straw that drove the livestock farmers and winegrowers into each other’s arms.

The vrijboeren challenged the VOC leadership at the Cape, also with the support of a certain Henning Husing. Incidentally, thanks to the meat monopoly this man once had and his close cooperation with the governor, he had risen from the rank of soldier to become the richest man in Cape Town. The same applied to Jacob van der Heijden, who had also acquired immense wealth in the political and economic system at the Cape prior to 1702. And even though the support of these two wealthy individuals was of course motivated by self-interest4, for most of the vrijboeren in the countryside – such as the Nine – resisting the VOC’s authority was a matter of utter necessity. In the spring of 1705, a secret brotherhood of vrijboeren took the decision to bypass the Cape government and to petition the VOC ‘s Heeren XVII with their grievances, first in Batavia (Dutch East Indies) and then in Amsterdam. Adam Tas, another rebel and ‘the one most gifted with the pen’, was chosen as secretary of this group. At that time he also began his now famous diary that describes everyday life and events that took place at the Cape. He had arrived in 1697 from Amsterdam and as a free burgher went to live with Henning Husing, his maternal uncle, for whom he also worked as a private secretary. Tas ended up becoming ‘a farmer’ because of his marriage in 1703 to Elisabeth van Brakel, ‘a rich farmer’s widow’ (see ‘ . . . Jacobus van Brakel’s Family’)5.

As many as sixty-three farmers signed the secret petition. But it did not remain a secret from the Governor for long. His brother Adriaen worked in Batavia as a member of the advisory Council of the Dutch East Indies. Once the complaint arrived there, he immediately notified his brother Governor Willem Adriaan. At the end of February 1706, the governor had a number of the vrijboeren – including Tas and Van der Heijden – arrested and thrown into prison, at times without daylight or visitors. Meanwhile, he continued to pursue his other opponents at home with ‘fire and sword’ – particularly the Nine – at times resulting in deaths. According to the astronomer Peter Kolbe – who arrived at the Cape in 1705 and also provided a detailed description of day-to-day life there – three of the Nine died in that period. Furthermore, by making use of ‘a carrot and a big stick’ or in other words rewards and punishment, Willem Adriaan immediately collected 240 signatures for a counter-petition. As far as he was concerned, providing absolute proof of ‘his righteous behaviour that would surely convince the Heeren XVII. Moreover, in Amsterdam everything would be clearly explained by a group of ‘four fair-minded petition signers’ – the so-called belhamels (rabble-rousers), which happened to include his close associate Husing. And so it went, but the governor had overplayed his hand.

A fleet departed for Amsterdam on 31 March 1706 with this group aboard, the counter-petition and of course the petition of the vrijboeren. Barely on their way, Willem Adriaan had a change of heart. He was determined to stop the fleet, but a strong south-easterly wind had already blown the vessels too far ahead; it was an unfavourable omen. After four months at sea the ships arrived on the North Sea island of Texel. A committee examined the documents and also heard testimony from Husing and the others. The upshot was that at the end of October 1706 the Heeren XVII banned their civil servants at the Cape from ever being involved in trade or agriculture again. In addition, they recalled Van der Stel and a number of other ‘public servants’ from his clique and promptly replaced them. The actions of the vrijboeren were deemed justified and the sentence of ‘The Nine’, who had been convicted in absentia (to a fine of 200 rijksdaalders, exile to Mauritius for five years, and banned from holding any kind of public office) was commuted. The verdict reached the Cape at the end of February 1707, but a deeply dismayed Van der Stel delayed the public announcement. After being replaced and taking his sweet time to leave, in April 1708 he returned home to the Dutch town of Lisse.

‘The Nine’ Vrijboeren

In honour of the 300th anniversary of the Dutch Reformed Church of Stellenbosch, in November 1986, the community took a look back at their modest beginnings: ‘There was a small group of people with families who wanted to provide an education for their children. Of these people, who were fifty-two in number, that first religious community was formed’6. The church then got an enormous boost when a group of Huguenots joined the community: they had arrived at the Cape in search of religious freedom because the French King Louis XIV had revoked the Edict of Nantes in 1685.

It is striking that just ten years later, at least half of the names of the Nine can be found amongst those listed on the Board of Trustees of churches both in Stellenbosch and at the Cape. They were apparently considered model citizens by then and Faith, Necessity and Hope often brought them together. In this regard, Peter Kolbe points out ‘that of the nine colonists – forced to flee because of their involvement in the rebellious complot – three were Afrikaners (first settlers), three Frenchmen (Huguenots who had fled France) and three Dutchmen (recent arrivals)’. He further points out ‘the strange coincidence that one Afrikaner, one Frenchman and one Dutchman died; hunted down by the governor’s men.

Who exactly were these nine men on the judiciary’s list? Die Groot Afrikaanse Familienaamboek (Lit. The Big Afrikaner Family Name Book) published in 1983 by the genealogist Cornelis Pama discusses almost 3000 early South African families and provides the following details: the year they arrived at the Cape, legal name, and the family’s origin:

| Year | Name | Origin |

| I. | The Afrikaners | |

| 1656 | 1. Jan Elbertsz | Father: Hendrik (Heinrich), ‘adelborst (young noble) from city of Osnabrück (Germany)’ |

| 1656 | 2. Claas Elbertsz | Same |

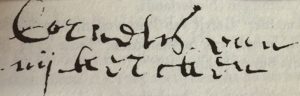

| 1671 | 3. Cornelis van Nieukerk | ‘Possibly from Nijkerk on the Veluwe (Dutch Republic)’ Signature: Cornelis van Nijkercken |

| II. | The Frenchmen | |

| 1688 | 4. François du Toit | Van Rijssel / Lille (France). Du Toit = ‘of the Roof’ |

| 1688 | 5. Guilliam du Toit | Same, ‘Guillaume’ |

| 1688 | 6. Hercules des Pre | Van Kortwijk (Dutch Republic/Belgium). Du Prez = ‘from the Meadow’ |

| III. | The Dutchmen | |

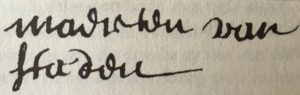

| 1686 | 7. Marten van Staden | From the city of Haarlem (Dutch Republic), ‘Maarten’ |

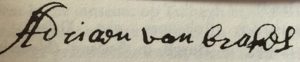

| 1698 | 8. Jacobus van Brakel | Father: Adriaan, from the city of Den Bosch (Dutch Republic); died in 1698 |

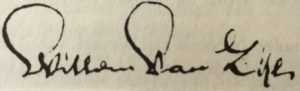

| 1699 | 9. Willem van Zeil | Village in South Holland. Signature: Willem van Zijl |

5. The origins of ‘The Nine’ Vrijboeren

Also worth mentioning is that the signature of each man appears beside his name, but sometimes the spelling deviates from the judiciary’s list. As of 1691, the Cape population with European roots was: two-thirds Dutch, one-sixth French, one-seventh German, and the rest were Swedish, Danish and Belgian7.

The 1882 publication Geslaregisters van die ou Kaapse families (Genealogies of Old Cape Families), by the so-called father of South African genealogy C.C. De Villiers et al., provides an extensive genealogical overview of the families then living at the Cape. It clearly indicates that these families intermingled more and more. Striking about all the families of the ‘Nine’ is that they were closely affiliated with the church and involved in agricultural endeavours. Of course, in view of the VOC’s emigration selection policy in those years, this is not so surprising. Also striking is that some of the ‘Dutch’ families discussed in this article already knew each other before they emigrated to the Cape – again through the church and work, which was often the case. To take a closer genealogical look it seems best to focus on these four families, without the intention of negating the significance of the others. Specific details related to the different family backgrounds of especially the Van Nie(u)(w)kerks will be examined more closely, given that until now the connection between this family in the Netherlands and the one in South Africa was not very clear.

A side-note about the French: after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes by King Louis XIV in 1685, the Huguenots were persecuted and faced the choice of returning to the Catholic ‘Mother Church’ or holding on to their Protestant religious convictions and emigrating. Until 1710, as many as 300,000 decided to emigrate, of which 70,000 chose to go to the Dutch Republic. Given the VOC policy on accepting newcomers, 156 Huguenots travelled to the Cape in 1688, mostly families. Ten years later, that number had risen to over 200 and eventually to 270. Forty Huguenot family names South Africa have been passed down and are still in use today.

From Cornelis van Nijkercken to Cornelis van Nie(u)kerk

The Family

I initially considered the oral history passed down in my agricultural and Protestant family, which has its roots in the Westland region of the Province of South Holland. These stories date back to the early 17th century to the family of Willem and Cornelis Folkertsz. van Nijkercken in Neerlangbroek in the province of Utrecht, just south of the villages of Doorn and Leersum. This area was a familiar, trusted setting for the family for centuries. Also illustrative of this: when my grandfather Gerrit was forced to evacuate due to the construction of coastal defence (Atlantic Wall) at the beginning of WW II, he went to live with ‘the farmer [de Geer] in Leersum’. He died there in 1950 8. Later in the war my father went into hiding there to escape the Arbeitseinsatz (labour deployment by the German occupier). A second aspect of this oral history concerns the family name in relation to religious conviction: the Van Niekerk branch was predominantly (and remained) Roman Catholic and originally lived in and around the city of Utrecht. Later they mainly lived in the west of the province of Utrecht and in the province of South Holland9. In contrast, the Van Nieuwkerk branch primarily practiced (or converted to) the Protestant faith.

6. The Church of Neerlangbroek (1732)

In 1640 the aforementioned Cornelis Folkertsz. van Nijkercken was an armmeester (caretaker of the poor) and the deacon of the Dutch Reformed Community of Neerlangbroek from 1642-1643. He held this position with Elder Conradus (Coenraad) Borre van Amerongen, Lord of Sandenburg – Utrecht nobility. Cornelis later fulfilled the position of church elder a number of times and he also served in local government. He made his living as a carpenter and also farmed land south of Neerlangbroek, on which he grew buckwheat. Likewise, Willem Folkertsz was also a church elder (1668-1673), served in local government (1677) and worked a number of plots of land as a tenant farmer. They both belonged to a branch of the Van Nijkercken family that for 100 years from 1640 10 held positions in the church and public administration of Neerlangbroek and the surrounding area:

1. Aelbert Volkensz. vNK Carpenter and civil servant in Doorn, buyer of ‘wheat on the field’

2. Cornelis Folkertsz. vNK Carpenter NLB, tenant farmer, caretaker of the poor, judge, deacon, church elder

3. Gerrit Volkertsz. vNK Carpenter NLB, tenant farmer, churchwarden

4. Willem Folkertsz. vNK Tenant farmer of diverse plots of land, judge, elder

5. Aert Volkertsz. vNK Carpenter NLB, tenant farmer, elder

6. Maeijchie Volkerts vNK NLB, buried 1688

7. Gerrichje Volkerts vNK NLB, 3rd marriage to Jan Gerritz. van Velpen [Vulpen], deacon

8. Rijckje Volkens vNK Doorn, widow of Jan Janz. van Velpen [Vulpen]

7. The Van Nijkerckens [vNK] of Neerlangbroek [NLB]

Some other connections: Around 1682, Aelbert’s children arranged financial support for him in his old age through Deacon Marten van Staden of Doorn, who emigrated to South Africa a few years later in 1686. Cornelis along with his son Gerrit Cornelisz. and grandson Cornelis Gerritz are the link to the South Africa branch of the family11. Willem is the link to the family from the Westland (Dutch Republic).

The father of Aelbert’s family was Volcken Rijcksz., still without the ‘family name’ Van Nijkercken. He was also a carpenter and a tenant farmer in Neerlangbroek. His father was Rijck Volckensz. and his grandfather Volcken Rijcksz., who ‘at around the age of seventy years’ bore witness regarding a matter at the request of the Lord of Moersbergen. Therefore he was born about 1503 and was the ‘Patriarch’of around sixteen generations.

The Family Name

This surname denotes a place with a name derived from Nieuwe Kerk (Lit. New Church). In the Netherlands alone, this could apply to more than ten places12. I believe the city of Nijkerk is the most likely candidate, not only due to the name itself but also the location’s history and geography. Nijkerk is twenty-eight kilometres north of Neerlangbroek and twenty-five from Doorn – within easy walking distance in a day. The name Nijkerk means New Church and it is assumed the church was founded there as a daughter of the church of Putten, in any case before 1313. As a border town of the Duchy of Gelre and the Diocese (Utrecht), it was regularly the battleground of wars that caused immense destruction. Nijkerk also experienced its fair share of other disasters: flooding from the Zuiderzee (Lit. Southern Sea) and raging fires. The church burnt to the ground in 1421 and in 1540 the entire city was destroyed by fire. This last disaster might have led the family to choose for the countryside (around Neerlangbroek). Further information is not (yet) known about this.

Besides these factors, religious-political developments in the 16th and 17th centuries were also significant for the area. In the Middle Ages, the church of Neerlangbroek belonged to the Cathedral Chapter of Utrecht, a college of clerics (chapter) formed to advise a bishop. On 26 August 1581 the Staten van Utrecht (governing body of Utrecht) forbade the Roman Catholic worship service in the Diocese and recognized Dutch Reformed doctrine as the one and only public church. But under the secular doctrine of the libertine (freethinking) regents, this ‘reform process’ was hardly enforced. That was why a ‘visitation committee’ was set up, which in 1593 called on Neerlangbroek and churches in surrounding area as well13. Thirteen years later, during the first provincial Synod (governing assembly) in 1606 of the Utrecht church, the then pastor of Neerlangbroek reported ‘that the audience is considerable and growing’. As a consequence of the Synod of Dordrecht in 1619 the reins on the new church were tightened. From 1648, the religious community ‘is called upon to account for itself, daresay that for thirty or forty years the church’s situation was very lamentable. Things clearly improved in the Dutch Reformed community from then on: while in 1640 there were only eighteen communicants, ten years later that number had increased to sixty.

The geopolitical situation at the time was another major influence on the region. The Dutch Republic had waged war (at sea) against England many times and France and the Dioceses of Münster and Cologne (today Germany) subsequently joined forces with England in 1672: the Disaster Year. Apparently, the French King Louis XIV had not only a penchant for oppressing and persecuting his own subjects (such as the Huguenots years later) but those living in the Dutch Republic as well. Author F.C. de Rooy wrote that ‘The French occupation from June 1672 to November 1673 cost many lives. The village of Neerlangbroek suffered such devestation that for more than fifty years it no longer appeared in the Restantenlijsten (Lit. ‘Remains list of property and goods) of the area, no doubt indicating that there were no remains!’14 The minutes of church meetings also reveal that from 31 August to 5 October 1673 ‘Because of the looting of the French, no services could be conducted’. Important documents, money and goods ‘. . . are safeguarded against the eventual hazards of war as far the walled city of Wijck [bij Duurstede]’, where apparently there was less of a threat. The contemporary Dutch historian Luc Panhuysen wrote about this: ‘The entire countryside was continuously exposed to the plundering of passing military units. The brutality of the soldiers is more extreme there than in cities15.’ This devastation resulted in almost all the village’s seventeenth century municipal registers being lost to posterity. Meaning that other – secondary – sources have to be consulted for genealogical research.

From the (incomplete) parish registries available one still can conclude that the surname of the Van Nijkercken family was first noted down by the presiding pastor of the church in 1666 when ‘Anthoni Cornelisz. van Nieuwkercken’ was appointed deacon. He was the brother of Gerrit Cornelisz. (the father of the Cornelis Gerritsz. who emigrated to South Africa). The reason for the (delayed) use of the full surname can possibly be explained by an increasing number of names – particularly related to church positions – due to the rapid growth of families.

Cornelis Gerritsz. Van Nijkercken16

Cornelis placed this signature in South Africa, according to Pama. It is clear that he used the Dutch surname in full. Also in 1727 his son was given the full name Gerrit van Nieuwkerken. In legal documents related to the Farmer’s Rebellion the name is spelled Van Nieukerk and by later offspring Van Niekerk.

De Villiers and Pama mention that in 1671 two brothers, Dirk and Jacob van Niekerk, and a seun (boy) Cornelis arrived at the Cape as settlers. ‘It is not clear if Cornelis was the son of one of these two brothers; he could have also been their nephew.’ The brothers later returned home, but Cornelis stayed on and became the forefather of the Van Niekerks of South Africa. ‘The names Dirk and Jacob are not found amongst Cornelis’ children or grandchildren’s names.’ Maybe they were Cornelis’ uncles, but in any case they left and Cornelis stayed – in many ways ‘his own man’.

How old was Cornelis in those days? He had apparently reached an age where he was independent enough to make the trip and then to stay, but still a seun – or a boy. Of course, a boy in the seventeenth century was already fairly grown up: every VOC ship had a few cabin boys aboard, between ten and seventeen years old. The famous Dutch admiral Michiel de Ruyter started working as a cabin boy at the age of eleven. If we assume that Cornelis was around eleven to sixteen years of age, he would have been born between 1656 and 1660. He married Maria van de Westhuijsen in 1691 and would have then been about thirty-one to thirty-five years old, while the average groom in those days was about thirty years old. He died in 1710, so not yet sixty years old, which possibly explains why he was not ‘written off’ for the Schutterij (Town Watch), which at that time was normal there after one’s sixtieth year.

Cornelis’ father was Gerrit Cornelisz. van Nijkercken and his name appears in documents in Neerlangbroek and Doorn from 1657. He was most likely married for the first time (date unknown) in Neerlangbroek, where he leased plots of farmland. In 1662 he lived in Doorn, where his name appears from 1669 as being married to the widow of Teunis Stevensz. van Leersum: Grietgen Gerritsdr. Spijcker. Gerrit van Nijkercken succeededGrietgen’s first husband as innkeeper and host of the ‘De Vergulde Engel’ (The Gilded Angel) in Doorn17. This marriage literally and figuratively exposed this Van Nijkerken branch to the ‘wider world’ and particularly to South Africa, given it provided access to lots of information and contacts. Much like what the Emigration Centre did for my bother in 1962, so one got to know how things worked across the sea. To begin with, in 1640 Teunis’ brother was in the service of the VOC. Griegten’s brother, whose name was also Cornelis, lived in the Amsterdam where the VOC was headquartered and as Teunis’ co-heir was often consulted by the family. Everyone also had close ties socially and religiously. Teunis van Leersum left seven children from his marriage with Grietgen. The oldest was Steven and he was born around 1650. He married Maria Cornelis Volkertsdr., the sister of his stepfather Gerrit Cornelisz. and the widow of Peter Ponsz. van Velpen. The sixth child was a daughter born around 1660. Her name was Aletta.Striking was that Cornelis Gerritsz. with his father Gerrit Cornelisz. (her stepfather) came to live with her family in Doorn and they were about the same age. As a result, they may have developed a close relationship, like ‘brother and sister’, which they apparently also maintained via the ‘post’ (which took at least four months) after Cornelis left for the Cape. Because in the early 1690s when Cornelis’ first child, a daughter, was baptized, she was named . Aletta! Their second child was a son who – less surprisingly – was called Gerrit. Apparently others were also very fond of Aletta because in 1685 Aletta was a witness at the baptism of son Wilhelmus [= Willem] from Maarten van Staden of Doorn. This was the very same Van Staden who as a deacon had helped Aelbert Volkertsz. van Nijkercken (see ‘Countryman Maarten van Staden’) and also took part in the Farmer’s Rebellion in South Africa with Cornelis Gerritsz.

Cornelis settled in South Africa northeast of Cape Town, near the hilly area of Tygerbergen18. His farm was located near Elsie’s Kraal, close to present-day Bellville , more or less on the border of the three districts Cape, Stellenbosch and Drakenstein. When Landdrost Joannes Starrenburg set out with sixteen to twenty soldiers on 2 October 1706 to throw him and others ‘into some dark hole’, Cornelis ‘had apparently already fled to Drakenstijn’, and further. He died in 1710 and was buried in Tygerbergen.

8. The Van Niekerk Street intersecting the Van Der Stel Street in Bellville

‘The Van Niekerks are one of the old families in South Africa, followed by scores of descendants that spread throughout the entire country. Early on, several family members settled in the northwest, others moved to the eastern border districts and, consequently, many took part in the Great Trek’19 (Dutch-speaking colonists’ movement – around 1835 to 1846 – up into the interior of southern Africa in search of land where they could establish their own homeland, independent of British rule).

Nowadays Marlene van Niekerk – born on the plaas (farm) Tygerhoek near Caledon – ¬is not only a well-known South African writer but also a celebrated author in the Netherlands20. In the wine maker’s industry, the brothers James (viticulture) and Hansie (marketing) van Niekerk with his son Barry (winemaking) are an example of excellence in their field, along with their wives Ingrid and Carol (guesthouse). Together they run the family’s beautiful wine estate Knorhoek (‘The place where the lions growl’: a reference to the wild landscape) which encompasses 105 hectares and is located between Stellenbosch and the village of Klapmuts (www.knorhoek.co.za). The estate dates back to 1694 and since the middle of the nineteenth century the sixth generation of Van Niekerks is connected to the family wine business21.

Also Countryman Maarten van Staden Crossed the Sea (1686)

Maarten (Marten) van Staden, according to Pama, placed this signature in South Africa. He was born around 1636 somewhere near the city of Haarlem and villages of Bloemendaal and Overveen. He studied horticulture and may be related to the Van Staden family that – as so-called Hoveniers ten Hove (Horticulturists of the Court) – served not only the owners of the country estates along the River Vecht in the seventeenth and and early eighteenth centuries, but also the Dutch Royal Family at home and abroad22. He married twice. His first marriage was to Margaretha (Maria) Ernstdr. van Amerongen in the early 1670s. In 1675 their son Martinus was born; Maria died that same year, probably due to complications associated with childbirth. Maarten remarried Catharina Willems in 1677 in Werkhoven, less than five kilometres from Neerlangbroek. She was from Giessen-Nieuwkerk – near Gorcum – and was born there around 1647. Maarten worked various places as a landscaper: in Werkhoven (1675-1680) around the time of his marriage and then in Doorn (1680-1685) at the manor house Huys te Doorn. In those days, it was owned by Caius Laurentius Barthram, son of the Count of Broeckdorff. The house was around the corner from the church in Doorn where Marten was, as already mentioned, deacon. In 1685 he decided to emigrate with his family to South Africa. His sixth child Willem had just been born and with all their children in tow Maarten and Catharina arrived at the Cape of Good Hope in 1686. The family grew in their new country to finally included nine children: Martinus (1675), only child from first marriage, Maria (1678), Maurits Louis (1680), Johannes (1681) (Jan), Caspara (1683), Willem (1685), christened 15 March 15 in Doorn with Aletta van Leersum as witness – and in South Africa: Elisabeth (1688), Elisabet (1690) and Petronella (1692).

Martinus, from Marten’s first marriage, also went to the Cape with his father. In 1705, his father and stepmother stated in their will that in word and deed he meant so much to the family that upon their deaths he would inherit the same portion as his other siblings.

As farmer, in 1687, Marten was granted a piece of land that he named Bloemendal, in what would later become the Simondium District of Drakenstein (today Paarl). A second property, Overveen (about 50 hectares), was also granted to him on 28 April 1695. Striking are the name choices of these properties, which refer directly to his Dutch origins23. He was honoured on several occasions by being appointed one of Drakenstein’s Heemraden (town officials). In 1703 he also served as a church elder. But the Farmer’s Rebellion in 1705 forced him to flee. There are no reports of him being imprisoned, as with some of the other Nine Vrijboeren, including a certain Jacobus van Brakel. According to the registries of Drakenstein, Marten died in 1716 (around the age of eighty) and Catharina a year later (around the age of seventy).

Their son Willem had a daughter Anna who married Johannes van Niekerk in 1738. It was his second marriage. He was the third child of Cornelis Gerritsz. van Niekerk and Maria van der Westhuijsen, after Aletta and Gerrit; their younger children were Peter, Helena and Bernardus.

The Tragic End of Jacobus van Brakel’s Family (1707)

This signature of Adriaan Willemsz. van Brakel, who was the father of Jacobus, also appears in the Groot Familieboek by Pama. Adriaan was born in 1640 and originated from Den Bosch. He married Sara van Rosendael (born c. 1650) in South Africa in 1670. They had fourteen children, of whom more than half died prematurely. In addition to Elisabeth (1674), Maria (1677) and Hermanus (1688), also three Jacobuses were baptized: respectively in 1676, 1679 and 1681. I have chosen 1681 as the year ‘our’ Jacobus was born. Father Adriaan, also according to Pama, was initially a livestock farmer but later became a suikerbierbrouer (beetroot beer brewer). He served as an elder of the Cape religious community a number of times and ‘is a well-off man who owns six paintings’. His wife Sara died in 1690 and he followed in 1698. Sons and daughters then shared in the family wealth, because not only James and Hermanus later owned farmlands but also his sister Elisabeth who became a ‘well-to-do lady farmer’. In 1703, as a widow, she married Adam Tas, who according to those who opposed him ‘could not have been a luckier man’. They also had four more children, but she passed away at forty years of age (1714).

According to a detailed account given by Peter Kolbe, Jacobus’ life ended tragically. After the death of his father, in 1702 he married Margaretha Elberts, a sister of Jan and Claas Elberts – who later also took part in the Farmer’s Rebellion with Jacobus. Margaretha had been baptized in 1686, so at the time of their marriage she was sixteen and the bridegroom was twenty-one. As one of the Nine vrijboeren who rebelled, in 1705 Jacobus was forced to flee. The governor ordered Landdrost Starrenburg and his men to quickly go in pursuit. At the beginning of October 1706, Van der Stel reported a failed attempt to ‘capture Cornelis Nieukerk at Elsie’s Kraal and Jacobus van Brakel at Moddergat’. They had already ‘run off that same night to Drakenstijn’, to meet up with Willem du Toit and Hercules des Pre and head onwards from there to the Vier-en-Twintig Riviere (‘called this because of the twenty-four streams and rivers’), a harsh landscape north of present-day Johannesburg.

A few months later, Van Brakel as well as Des Pre were finally located. Jacobus was arrested with Des Pre at the beginning of February 1707 while he was ‘cleaning Koorn en Tarwe (harvested wheat) in front of his house’. Perhaps the news from Amsterdam about the conviction (in October 1706) of the governor and his entourage, including the Landdrost, had become public knowledge and this had caused the rebellious farmers to let down their guard. Just like in the Dutch Indies, there was also the phenomenon of rumours travelling – as if carried by the wind – much faster than ships24. The official letter finally arrived at the end of February. Or perhaps letting down his guard had more to do with his home situation: Jacobus’ wife was ‘heavy with child’ and his three-year-old son was ‘knocking at death’s door,’ according to Kolbe. In any case, the Landdrost ordered his men to destroy all the household belongings and his two prisoners were carted off to the Cape, where the men were immediately condemned and imprisoned. The panicked wife of Jacobus also travelled to the Cape with her sick son, but could do nothing more for her husband. It was the terminally ill son who ‘paid the ultimate price. The mother was so shaken by his death that she went into premature labour and twenty-four hours after giving birth to a stillborn, died herself.’

Six months later, Jacobus followed his wife and children to their graves (she was only twenty years of age and he twenty-five), ‘which at the Cape was seen as the result of the unrelenting rage of the Lord Governor and the Landdrost.’

Willem van Zijl: Remorse and Ultimately Success

According to Pama’s book, Willem did not sign his name simply as Zeil, the way it appears in Cape legal documents, but with the so-called long ij. Willem was born in 1668 in the vicinity of Delft25. His surname was probably taken from the River Zijl, a branch of the river Oude Rijn near Leiderdorp and flowing to the Kagerplassen, a small lake system in South Holland. He trained as a horticulturist and came to live in Amsterdam for his work. There he met Christina van Loveren, with whom he became engaged on 12 November 1694. He was then twenty-six years old and Catholic; she was twenty-one years old and her background was Protestant. Shortly after their marriage, the couple moved to Haarlem – probably for his work – where their first child Wilhelmina was born in 1695. Their second child Albertus saw the light of day two years later in Velzen to the north of Haarlem, an area with many summer estates and bleekerijen (facilities for bleaching linen). Apparently the wider world seemed a lot more interesting to them, perhaps because of the stories told by William’s brother Frans, who was employed by the VOC as a soldier. Through him they heard that people willing to emigrate to South Africa were eligible for free passage, if they were prepared to stay at the Cape to farm for at least fifteen years. They departed with their two children on 22 September 1698 from the North Sea island of Texel, aboard the ship De Drie Croonen, which travelled in a fleet of seven ships. That these trips were hard is apparent from the fact that as many as twenty-seven passengers died during this voyage. After almost four months at sea they arrived on 23 January 1699 at the Cape of Good Hope. Willem initially worked as an ‘supervising gardener’ in the service of the VOC at the property Rustenburg near Rondenbosch. In 1700 he was granted the rights to two plots of land on the Langstraat in Cape Town. Within three years he became a free burgher and acquired the magnificent wine estate Vrede & Lust (Lit. Peace & Joy: www.vnl.co.za) – the first half in 1702 and later the rest. He went into debt to do this. The family grew quickly; there were finally nine children: Wilhelmina (1695), Albertus (1697), Johannes (1700), Hendrina (1701, died at a young age), Gideon (1703), Pieter (1706), Hester (1708), Christina ( 1709) and Johanna (1718). All four sons took part in the Great Trek – partly because there was less and less land available to farm – and they were the forefathers of large South African families with many descendants. Father Willem became an influential citizen both in the military and public life. In 1703 he was promoted to Lieutenant, under the command of Captain Hercules des Pre, and in 1706 he was appointed Heemraad (Alderman).

In that same year Willem also signed the petition against Van der Stel. As a ‘semi-authority’ he was presented with a difficult choice: to be loyal to the rebellious farmers or to the despised government authority. As mentioned earlier, the governor used ‘a carrot and a big stick’ to collect around 240 counter-signatures that supported his policies. Willem van Zijl’s signature is found amongst these as well. Is this because he was intimidated like Klaas van der Westhuijsen (brother-in-law of Cornelis van Nieukerk) who was imprisoned for three months and threatened with being exiled to Mauritius? Or perhaps he was misled and deceived into signing? ‘The statement of the 240 free burghers attests to nothing more than the Lord Governor being an honest man, about whom people did not have a bad word to say.’ In any case, Kolbe mentions that on 19 February Willem testified in support of Van der Stel but almost immediately felt remorse and on 24 February once again expressed his support for the vrijboeren. And that meant he, like the other Nine, had to go into hiding to avoid prosecution. He also chose ‘to flee and take refuge in the bush of ‘Vier-en-Twintig Riviere’. By the middle of 1707 it was safe for him to return to his family. He then successfully expanded his businesses and also worked dedicatedly for the community; in 1719 he was appointed to the sought after position of Heemraad again. Willem died in 1727.

Conclusion

The rebellion against Willem Adriaan van der Stel ended once and for all with his early return home to the town of Lisse. Just before departing for Europe he spoke with Peter Kolbe. Apparently he was still extremely offended and said that the rebellion against him was ‘exclusively a farmer’s movement, born of farmer’s grievances’ and ‘. . . they set me up to take the fall.’

As fate would have it, Van der Stel was actually the one who made the vrijboeren into a unified force, overwhelmingly united against him. The rebellion strengthened their self-confidence and was a first step to self-determination. Two centuries later that same resolve would also be reflected upon in the House of Commons. The British politician Boris Johnson related a story in his 2014 biography about Winston Churchill: how he had briefly been a correspondent during the Second Boer War (1899-1902) and that he was remarkably pro-Boer in his maiden speech: ‘. . . if I were a Boer. I hope I should be fighting in the field’ – ironically against England.

An additional outcome of the Farmer’s Rebellion was that the farmers who found their way in the wilderness planted the seeds for the later and much-freer vrijboeren of the Great Trek. But that is a another story!

The research for this article also revealed that South Africa’s European immigrants frequently interacted with one another and that their families intermingled. Relations with the home country were considered extremely important and family ties were maintained. This was also clearly reflected in the close relationships the Dutch ‘home front families’ had with one another before, during and after the emigration of their relatives.

Image Sources:

- Photo: mariusvannieuwkerk.

- University of Amsterdam Library

- Portrait by the Dutch master Pieter van Anraedt, possibly 1672, Wikipedia.

- Drawing: Kroniek van Nederland (Chronicle of the Netherlands), Agon, 1987.

- Pama, C., Die Groot Afrikaanse Familienaamboek (Lit. The Big Afrikaner Family Name Book), South Africa, Human Rousseau, 1983.

- Drawing: Louis Philippe Serrurier 1732 (The Utrecht Archives)

- Genealogical Archive of the author

- From: www.google.com/maps

- Photo: Léon van Zijl, 2013

Note: All the signatures of ‘The Nine’ that appear in this article are from: De Villiers, C.C.; Geslagregisters van die ou Kaapse families (Genealogies of Old Cape Families), completely revised edition reviewed and supplemented by C. Pama. Cape Town: Balkema, 1981.

NOTEN

1:

See also: Kroniek van Nederland< (Chronicle of the Netherlands), Agon, 1987; Dagregister van Adam Tas (Diary of Adam Tas), dnbl (Digital Library of Dutch Literature); Peter Kolbe, Naauwkeurige beschrijving van de Kaap de Goede Hoop (Detailed Description of the Cape of Good Hope (1727), Biodiversity Heritage Library; François Valentyn, Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indië (Old and New East Indies), 1724, including South Africa; Ad Biewenga, De Kaap de Goede Hoop, Een Nederlandse Vestigingskolonie, 1680-1730 (The Cape of Good Hope, A Dutch Settlement Colony) Amsterdam, 1999.

The Dutch pastor and seasoned traveller François Valentyn suggests that the estate Constantia was named in honour of Simon’s wife Gemaalinne who Simon left behind in Amsterdam. This seems very unlikely. She was called Johanna Jacoba Six and he was ‘estranged’ from her. He did, however, take her sister Cornelia along to the Cape. More plausible is that Simon’s private estate was named after a certain Constantia Louiza, the daughter of a high VOC official who had granted him the land. Willem Adriaan’s Vergelegen (Lit. Faraway) was given this name because it took three days by oxcart to get there from Cape Town.

De Wet, C. G., Die vryliede en vryswartes in die Kaapse nedersetting 1657-1707 (Free Burghers and Free Blacks in the Cape Settlement), 1657-1707, Cape Town, Historiese Publikasie-Vereniging, 1981.

Schutte, G.J., Kompanjie en kolonisten aan die Kaap (The Company and Colonists on the Cape), Cape Town, Historiese Publikasie-Vereniging, 1979, pp. 185-225.

Besides Adam Tas, there was another keen observer at the Cape in that era: Peter Kolbe was stationed at the Cape by the VOC from 1705 to 1713 to provide a ‘detailed description of the Cape of Good Hope’ from a scientific point-of-view. In addition to these two chroniclers, Reverend François Valentyn regularly travelled back and forth to the Dutch East Indies between 1685 and 1705 and enjoyed being welcomed by father and son Van der Stel at the Cape. While he was rarely lacking in words in his five-part encyclopaedia Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën (Lit. Old and New East-India) which descibed the history of the VOC and the countries of the Far East, he wrote very little about the Farmer’s Rebellion of 1705, claiming ‘it was not part of his job’.

Allemaal Familie www.allemaalfamilie.nl/mgd_allemaalfamilie.php?pageid=7649&langid=1

Besselaar, Gerrit, Zuid-Afrika in de Letterkunde (South Africa from the Literature), Cape Town, 1914, @2009dbnl.

www.dbnl.org/tekst/bess001zuid01_01/bess001zuid01_01_0001.php< /div>

With sincere thanks to my oldest brother Jan van Nieuwkerk.

This is also evident from my present-day personal exchanges as well as the rich genealogical research of Theo van Niekerk; see his 300 jaar Van Niekerk- Genealogie van een Rooms-Katholiek geslacht (300 years Van Niekerk- Genealogy of Roman Catholic Lineage), Paterswolde, 1986. According to him, the oldest ancestor of the Van Niekerk’s branch was Gerrit Dominicus van Nieukercken: born around 1675-1680, married in the Dutch city Vianen R.C. and buried in the Tolsteeg Cemetery (Utrecht) as Gerrit van Nukerk. Based on information from Vianen, Jos van Niekerk directed me to the possible father of Gerrit: Dominicus Gerritz. van Nieuwkerk married on 26 July 1674 to widow Annigje Aarts.

With my utmost thanks: partially based on verbal and written exchanges with Marcel Kemp and Wouter Spies, two experts on the genealogical history of the area surrounding the River Kromme-Rijn (Netherlands).

VC 603, Marriage register Dutch Reformed Church, Cape Town, p. 87: ‘On the 1st of April 1691 young man Cornelis Gerritz. van Nieuwkerk joined in marriage with Cornelia van der Westhuijzen young daughter of the Cape of Good Hope.’ Pama also mentions the Cornelis Gerritz. vNK as the forefather of the family in South Africa.

According to the Meertens Institute there are 11 places in the Netherlands, spread over 7 provinces, including 1 place in the province of Gelderland: the ‘town’ of Nijkerk. Also see my book Hollands Gouden Glorie (Dutch Golden Glory): www.mariusvannieuwkerk.com referring to the ‘drowned village’ of Nieuwerkerk in the Haarlemmermeer (1531-1740). In Belgium the Institute lists 4 places and for Germany there is ‘an entire list’.

‘Visitatie der Kerken ten plattelande in het Sticht van Utrecht ten jare 1593. . .’ (Church Visitations in the Countryside of the Diocese of Utrecht), Utrecht, Historisch Genootschap, 1884.

De Rooy, F.C., ‘Het geslacht De Roij alias Joncker in Neerlangbroek’ (The family De Roij . . .), in De Nederlandsche Leeuw 115, 1989, no. 4-6, pp. 95-117.

Panhuysen,L. Rampjaar (Disaster Year) 1672, Amsterdam, Atlas, 2009, p. 414.

With immense thanks to Ad Biewenga and Rina [Catharina Amelia] Brink for the verbal and written exchanges about the South African branch of the family.

According to the historical society De Oudheidkamer Doorn, this could have been located where the later Hotel-Restaurant ‘PABST’ stood. At the beginning of the 18th century there was already an inn on this spot, at the crossroads to Driebergen, Nykerk, Leersum and Neerlangbroek – with around the corner Huis Doorn where the former German Emperor Wilhelm II once lived. Twice a year his grandson came to stay in the hotel with his family. The inn at that time had a large stable for horses and carriages out back. The annual town fair was also held in the garden behind the house. Worth noting is that in 1654, Teunis van Leersum –Gerrit Cornelis’ predecessor as innkeeper – apparently still owed ‘money for hay’ to Gerrit Volckertsz., an indication that horses were already stalled there in the early days.

According to Valentyn: ‘They are called the Tygerbergen (Lit. Tiger Mountains) not because it is the natural habitat of this wild animal, but because of the dark or brown spots on the hills . . .’

‘’n Familie Geslagregister van die Van Niekerk Afstammelingen van Johannes Wilhelmus van Niekerk, born 26 May 1780, died 13 June 1863’ (Family Tree of the Descendants of. . .), prepared by great-grandson J.W. Van Niekerk Totiusstraat 7, Potchestroom, 1965.

Vertel me eens: waarmee gaan wij boeren, jij en ik? (So tell me again everything we’re going to farm with you and I?). A quote from a novel by Van Niekerk, Marlene, Agaat, Cape Town, Tafelberg-Uitgewers, 2004.

Later translated into Dutch (2006) and English (2010).

Their top brands are ‘Knorhoek’and ‘Two Cubs’. When asked about the family business, Hansie responded in a wine glossy magazine (2015): ‘What you see here is what people have worked for and achieved over time. There is no huge industry behind us and we are not wealthy businessmen having a little wine farm on the side.’

Aardoom, L. and Van Staden, C.P. ‘Tekenaar van het Loo, en andere van Stadens als Hoveniers ten Hove’ (Draftsman of Palace Het Loo and other Van Stadens as Horticulturists of the Royal Court).

At that time, there were beautiful gardens and bustling bleaching facilities in the vicinity of the city of Haarlem and the villages of Bloemendaal and Overveen. Bloemendaal was given its name in the sixteenth century by a family with the same surname. They lived in in a manor house in the dunes called Aelbertsberg – named after the Christian preacher Adelbert – and they replaced his name with theirs. Overveen was originally called Tetterode or Tetrode. Overveen literally means over het veen gebied (over the peat area): between the strip of dune sand where Haarlem is located and the dune region.

kabar angin (Indonesian for rumours), Dutch writer and adventurer Johan Fabritius discussing the wind-maren (stories).

Authors Moustache, Pama, De Villiers, Kolbe, and family (as well as Léon van Zijl)Incidentally, in the fourteenth century, a family Van Zijl owned a number of stone houses in Langbroek: ‘. . . the landowners in the reclamation areas have grown wealthier than those on the old cultivated lands; especially the descendants of the colonists in Langbroek have become prosperous.’Dekker, C., ‘The Brothers Willem, Gerrit and Gijsbert van Zijl, Domkanunniken (Cathedral Priests) in Utrecht in the Second-Half of the Fourteenth Century’, from the yearly journal Jaarboek Oud-Utrecht, 1981, pp. 61-84.